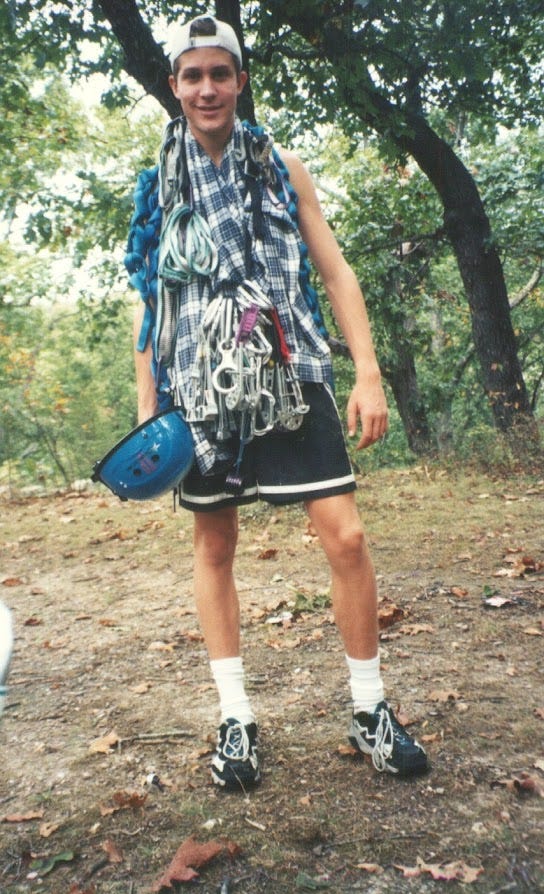

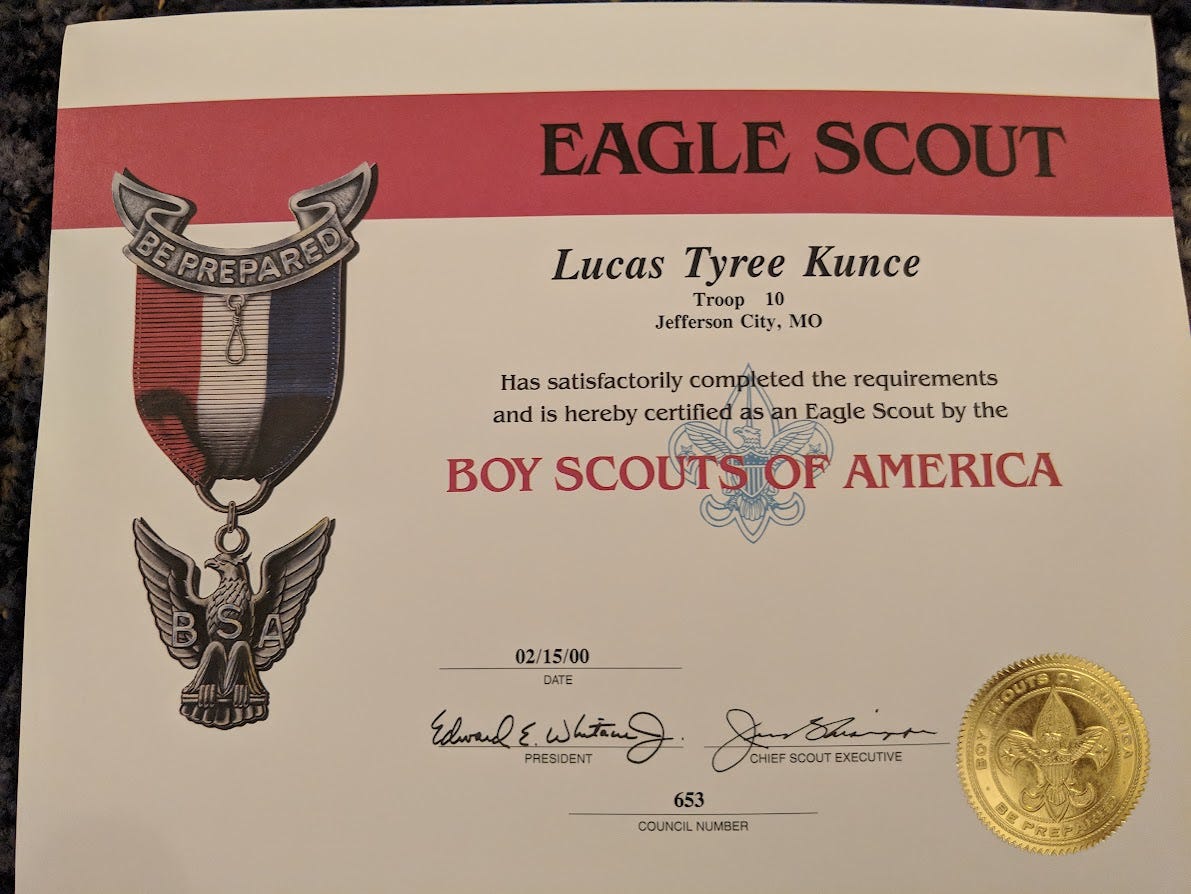

It’s time to put our next generation firstIf our leaders spent a lot more time investing in the next generation and a lot less time telling them what’s good for them, we would all be a lot better off.B is one of those guys that not a lot of people would think was very important. He was maybe 20 years older than me, but grew up right down the street and still lived about a mile away, on the east side of town in an area not a lot of people would want to live. Like the guys down at the Marine Corps League, B was a veteran. And, like them, B invested in his community. But that’s where most of the similarities end. B liked his privacy. He was more or less a loner, some might even say anti-social. Certainly no one ever called him inspirational. In the Navy he had done a tour or two as a submariner and when I was growing up he was a mechanic at a nearby coal power plant. He was a recovering alcoholic who had gotten in trouble with hard drug use at some point, cleaned up, and held his demons at bay with a steady stream of cigarettes. As far as I knew, his only interaction with the world beyond work, church, and the grocery store, was as my scoutmaster. B was a loner even as scoutmaster. He taught us how to use knives, rappel and belay, build fires, use a Dutch oven, and all the other scout skills, but otherwise kept to himself during anything more on the social side and let us more or less do our thing as long as we didn’t kill each other. Seriously, that was probably the line. When two other scouts and I were arrested by the railroad police for trespassing during one of his land navigation exercises (where B stayed at church as we wandered about town), I don’t even think we got a lecture. He just shrugged it off. He didn’t care if we won any of the scouting competitions, either. Which was good, because we never did. Despite his hands off approach and generally easy-going demeanor, there were two times we all knew you didn’t mess around with B. The first was when he didn’t have his nicotine. Either because he was half-heartedly trying to quit or because we were out on some long adventure and his supply had run out. Given the health implications for B, I’m embarrassed to say how selfishly and disturbingly grateful we were when he stopped trying to quit and how loudly we cheered when we pulled into that first gas station after B had run out of cigarettes seven days into a ten day Rocky Mountain wilderness hike. The second time you didn’t mess with B falls under the “as long as we didn’t kill each other” exception to his laissez-faire nature that I mentioned earlier: when we were at the shooting range. B had an arsenal, was one of those guys who loaded his own ammo, had been a competitive shooter for a while, and was a fiercely strict disciplinarian on firearm safety. Americans seem to be obsessed with the masculinity of firearms, and yet very few receive the type of training that B gave us so that we could truly use them well. He taught us safety first, second, and third, and then he taught us how to shoot every manner of handgun and rifle known to man and how to maintain the weapon systems responsibly. Regardless of his quirks, B truly invested in us, in our education, and our futures. I wouldn’t have been an Eagle Scout without him. We were a small, ragged troop that, like B, people would have looked down on if they’d even bothered to notice us. But it was an incredible experience. Most of the kids in the troop didn’t have much money, and the scout troop was how some of us saw more than our hometown. Missouri has incredible state parks and wildlife, and B took us camping and canoeing in every corner of the state. He put his own money into the troop, buying tents, stoves, and a trailer and drove us around in his station wagon. My dad often came along with the van, and that was enough for our tiny troop. Once a year we would even go outside the state. We went to Shiloh battleground one year, Colorado a couple of times, and occasionally to Philmont Scout Ranch in New Mexico. All because of B. He didn’t forget us either. When you’re just starting out as a young adult in the Midwest, one of the biggest quality of life and accelerators of success is whether or not you can get a car. Public transportation is poor to non-existent, and the ability to drive anywhere in town to find good work is huge. This problem was first solved for me right as I turned 16 when a guy down at church gave me an old car of his: a four speed manual with a worn out second gear. After six months of jumping from first to third, the third gear finally stripped and my mom and I scoured the classifieds for something we could get with the eight hundred or so dollars we managed to cobble together between my earnings and savings and some money she had saved. She was willing to pitch in if I agreed to drive my siblings around. We settled on a two-toned, cream and band-aid brown, 1985 Ford LTD with way too many miles. When it broke down the first time, B came over and fixed it while I watched. When I was 18, working through the summer in Louisville, Kentucky, it broke down again and, without B or the money or skill to fix it, I was in trouble. Eventually, a mentor of mine and chief do-gooder, T, who I had just met, paid for the repair. I paid him back at the end of the summer, but I swore that I would never find myself in that position again, remembering my parents’ struggles with car troubles over the years. The stress they went through. The pain of not being able to pay. I didn’t know if I’d ever have the money, but I could at least have the skill. I went to B for guidance. He gave me a cheap set of tools and a Haynes manual so that I could fix that car on my own. The next time it needed a repair, he walked me through it. Then he did it again. When my sister needed a car, he gave her his old beat up Crown Victoria with its worn out Haynes manual in the trunk. And when it broke down, he came over and we fixed it together until I learned. B gave me the tools to survive in the wilderness as a kid, and as a young man he gave me the tools I needed to stay on the road. I had numerous breakdowns in the various worn out cars I could afford during my early years and, because of B, every time it happened I was able to get out the manual, figure out the problem, hitchhike to a parts store, and fix it on the side of the road or the edge of a parking lot. I fixed my grandma’s car when it broke down. When my sister’s radiator blew in college and she couldn’t afford to fix it, I drove up and swapped it out with a new one like it was nothing. B never told us what to do. He didn’t tell us to be like him. In fact, if you’d asked him, he probably would have specifically told you *not* to be like him. Telling people what to do and how or what to be is folly (rhymes with Hawley… wonder why…). Investing in others is everything. Veterans, like the guys I met down at the Marine Corps League, B, and the men and women I served with for thirteen years in the Marine Corps, including three trips to Iraq and Afghanistan, understand that. The ethos is drilled into us at boot camp, officer candidate school, and every leadership course or lesson you’re ever taught. B understood it. And for a guy who probably kept all his cash under the mattress, B did a lot of investing in his life. In others. And I know I wouldn’t be where I am today without him. If our leaders spent a lot more time investing in the next generation and a lot less time telling them what’s good for them, we would all be a lot better off. ### |

Wednesday, August 28, 2024

It’s time to put our next generation first

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.